Over the last year, debate has increased over the issue of paying college athletes. Texas A&M’s Heisman-winning quarterback Johnny Manziel was suspended half a game for allegedly signing autographs for money. NFL Pro Bowl running back Arian Foster claimed he “took money on the side” in college to pay for rent and food. These, and numerous other recent controversies involving college athletes seeking to receive a slice of the enormous revenue pie that they’ve contributed to producing, have dragged the issue into the spotlight.

The National Collegiate Athletic Association’s (NCAA) bylaw 12.5.2.1 states that an intercollegiate athlete will be ineligible for participation if the individual “accepts any remuneration for or permits the use of his or her name or picture to advertise, recommend or promote directly the same or use of a commercial product of any kind.” This prevents colleges athletes from profiting off their own image, even though their colleges and universities actively do so. One such lucrative source of profit involving the athletes’ right of publicity is video games.

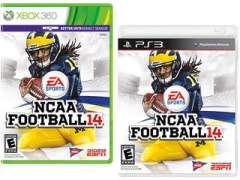

Last month, the video game company Electronic Arts (EA), released a statement claiming they would no longer produce a college football video game starting in 2014. EA has been producing college football video games carrying the NCAA name and the branding of its member schools since 1998. EA sells about 2 million copies of the NCAA game per year, alongside EA’s most popular games, the sports titles FIFA and Madden (which sell 12 million and 5.5 million per year respectively).

At the center of EA’s announcement that it will cease development of the NCAA game is the lawsuit In Re: NCAA Student-Athlete Name & Likeness Licensing Litigation. This consolidated case, most recognizably led by former UCLA basketball player Ed O’Bannon, alleges right of publicity and antitrust claims against the NCAA, the Collegiate Licensing Company (CLC), and EA for using their names and likeness in video games and television broadcasts without providing any compensation.

So what exactly is the right of publicity? The right of publicity is generally the right to prevent the “unauthorized use of an individual’s name, likeness, or other recognizable aspects of one’s persona.” It is largely protected by state common law,although some states protect the right with privacy or unfair competition statutes.. The elements of a right of privacy claim are generally (1) the use of a person’s identity; (2) for a commercial purpose; (3) without their consent; and (4) resulting in an injury.

In the current lawsuit, plaintiffs claim that the defendants misappropriated their likenesses in video games that distributed pursuant to license agreements with the CLC, NCAA, and NCAA member institutions. Although the games do not use their actual names or pictures, the athletes claim that EA used other similarities such as jersey numbers, heights, weights, skin tones, hair colors, and hometowns in the in-game biographical information for the players. These factors combined create a distinctive likeness that can be readily matched with real-life players—any college football fan can probably tell you who the digital avatars are meant to depict.

The First Amendment is commonly marshaled to defend against right of publicity claims. Video games are protected speech within the meaning of the First Amendment; however, the Third and Ninth Circuit found that the NCAA video games did not transform the players’ in-game identities sufficiently to dodge a right of publicity claim. Those courts prevented EA from effectively asserting First Amendment protection.

While some point out that athletes benefit from scholarships and the education they receive in return for being on the field, others argue the NCAA operates like a cartel, maximizing its own (and its member schools’) revenue on the backs of college athletes, while colluding to prevent these same athletes from seeking compensation elsewhere. But even if the current lawsuit succeeds on its right of publicity claims, the plaintiffs would only be compensated by third parties for use of their likenesses. It would not require schools to pay athletes in return for their services, which is the underlying issue behind O’Bannon’s antitrust claim against the NCAA.

Today, the NCAA is the lone defendant remaining in the case. Shortly after reports of a settlement arose, EA announced that it would no longer be publishing a new college football game for the upcoming year. The CLC, a trademark licensing and marketing company that represents over 200 colleges and universities in managing their marks, also settled. It would be surprising if the NCAA didn’t follow suit; a favorable decision for the plaintiff would set a precedent that could change the structure of college sports as we know it.

A timeline of the lawsuits can be found here: http://www.ncaa.org/wps/wcm/connect/public/NCAA/Resources/Latest+News/2012/September/Student+athlete+likeness+lawsuit+timeline